1. The Speech Chain

Key Concepts

- Human spoken language re-uses mammalian anatomy and physiology for vocalisation and hearing to create a communication system of complexity beyond any other animal.

- The form of speech is thus contingent on the nature of our vocal apparatus, our hearing, our cognition and our social structures.

- Speech science seeks explanations for the form of spoken language through study of the processes of speaking, listening, language acquisition and language evolution.

- Speech Science is an experimental science that sits at the crossroads of many other disciplines; it has developed its own explanatory models which have in turn been developed into many practical technologies.

- The Speech Chain is a simple model of spoken communication that highlights the transformation of an intention in the mind of the speaker to an understanding of that intention in the mind of the listener through processes that involve the Grammatical Code, the Phonological Code, articulation, sound, hearing and perception.

Learning Objectives

At the end of this topic the student should be able to:

- describe the domain of Speech Science as a scientific discipline within Psychology

- give an account of the speech chain as a model of linguistic communication

- describe the processes and knowledge involved in communicating information through the speech chain

- begin to understand concepts and terminology used in the scientific description of speech communication

- demonstrate insights into the size and complexity of language and the remarkable nature of speech

- identify some technological applications of Speech Science

- identify some of the key people in the history of the field

Topics

- Speech Science as a field of Psychology

The use of complex language is a trait unique to humans not shared by even our closest primate cousins. There is a good argument to be made that it is our facility for linguistic communication that has made human society possible and given us civilisation, arts, sciences & technology.

Although hominins have been around for about 5 million years, human language is a recent phenomenon, arising within the last 200,000 years at most; and except for the last 5000 years (when written language developed), human language occurred only in its spoken form.

A period of 200 thousand years is not long in evolutionary time, and there is little evidence that humans have a biological specialisation for spoken language; that is, the anatomical and neurophysiological structures we use for speaking and listening in humans are very similar to those we see in other primates and mammals. Instead, language seems to be a cognitive specialisation that has re-used existing anatomical structures and physiological functions to create a uniquely complex communication system that has been hugely advantageous for species survival.

But if our bodies have not evolved to support language, the form of spoken language must be contingent on the accidental form of our vocal apparatus, our hearing, our cognition and our social structures. We must conclude that speech has the characteristics it has because of biological happenstance: if our bodies had been different, then speech would have been different too. Speech Science seeks to understand how the physical character of spoken language arises from this biological contingency.

This contingency means that to understand spoken communication we must understand what constrains the form of speech and the use of speech. Partly that will involve a study of how our vocal apparatus generates sounds or of how sounds give rise to auditory sensations; but it must also involve the study of perception, memory and cognition generally. Information to guide our understanding will also come from the study of the form of language itself (Linguistics), and the study of how language is used to communicate (Pragmatics).

The study of spoken language thus sits at the intersection of many fields of enquiry: drawing on ideas from many other disciplines but also influencing their development in return.

- What does Speech Science study?

Speech Science is the experimental study of speech communication, involving speech production and speech perception as well as the analysis and processing of the acoustic speech signal. It deals with that part of spoken communication in which language takes a physical rather than a mental form.

Speech Science has its origins in Phonetics, which is the branch of linguistics that studies the sounds of speech. In this definition 'sounds' refers not just to noises but to the pieces of the linguistic code used to communicate meaning.

Speech Science differs from Phonetics in that it makes use of empirical investigations to develop quantitative explanatory models of the characteristics of speech sounds and the effects of speech sounds on the listener.

Speech Science asks questions like:

- How is speech planned and executed by the vocal system?

- How do the acoustic properties of sounds relate to their articulation?

- How and why do speech sounds vary from one context to another?

- How do listeners recover the linguistic code from auditory sensations?

- How do infants learn to produce and perceive speech?

- How and why do speech sounds vary between speakers?

- How and why do speech sounds vary across speaking styles or emotions?

Speech Science also provides the foundations for a multi-billion dollar industry in speech technology. Speech science concepts have value in building applications such as:

- Speech recognition. Systems for the conversion of speech to text, for spoken dialogue with computers or for executing spoken commands.

- Speech synthesis. Systems for converting text to speech or (together with natural language generation) concept to speech.

- Speaker recognition. Systems for identifying individuals or language groups by the way they speak.

- Forensic speaker comparison. Study of recordings of the speech of perpetrators of crimes to provide evidence for or against the guilt of a suspect.

- Language pronunciation teaching. Systems for the teaching and assessment of pronunciation, used in second language learning.

- Assessment and therapy for disorders of speech and hearing. Technologies for the assessment of communication disorders, for the provision of therapeutic procedures, or for communication aids.

- Monitoring of well-being and mood. Technologies for using changes in the voice to monitor physical and mental health.

- The Speech Chain

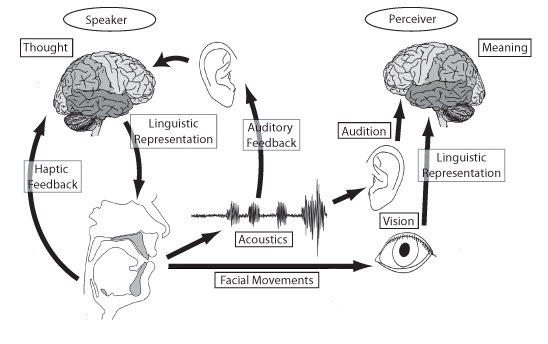

The domain of Speech Science is frequently described in terms of a diagram called "The Speech Chain". Here is one version of the speech chain diagram: [image source]

The speech chain describes the stages in speech communication whereby a message moves between the mind of the speaker and the mind of the listener. Through the idea of the speech chain we see that information which is communicated linguistically to achieve some goal is encoded by the speaker into a sequence of articulatory gestures which generate sound, that sound is communicated to the listener, processed by the hearing mechanism into a neural signal that is interpreted to extract the meaning of the utterance and the intention of the communicative act.

The main focus of Speech Science is on the elements of the speech chain that relate to:

- Encoding of pronunciation elements of the message as articulations (articulatory planning & execution)

- Aeroacoustic processes that generate sound from articulation (speech acoustics)

- Transmission of sound (acoustics)

- Audition of sound (hearing)

- Interpretation of auditory sensations in terms of pronunciation elements (speech perception)

As well as the audio channel between speaker and hearer, the speech chain diagram above also demonstrates other channels of information flow, in particular:

- Auditory feedback from the speaker's mouth to the speaker's ear. This flow of information is crucial when we are learning to speak, since it provides us with knowledge of how different articulations create different sounds. Children who are born deaf find it much more difficult to learn how to speak than hearing children. Auditory feedback also provides a means to monitor the quality and intelligibility of your speech production. The speech of adults who lose their hearing can become impaired as they lose the ability to monitor their own articulation.

- Visual information of the speaker's mouth movements can be useful to the listener, particularly in poor listening environments. We are all skilled lip-readers, and find it easier to understand speech in noisy settings when we can see the speaker.

- Speech Communication

Within the speech chain we can identify these main processing stages and the knowledge that speakers and listeners use at each stage:

Process Knowledge Intention Decide how to achieve effect in listener World knowledge, empathy with listener Meaning Create utterance having required meaning from words The Grammatical Code: meanings of words, grammar Utterance Look up word pronunciations in mental lexicon, decide on prosody The Phonological Code: pronunciations of words, meaning of prosody Articulatory plan Execute motor plan for articulator movement Auditory consequences of articulation Articulation Aero-acoustic properties of articulation Sound Propagation of pressure waves from speaker to hearer. Stimulation of auditory system. Auditory response Explanation of audition in terms of word sequences Auditory consequences of articulation, pronunciation of words, likelihood of word sequences Word sequence Recover utterance meaning from word sequence Meanings of words, grammar Meaning Recover intention of speaker World knowledge, empathy with speaker Understanding Let's look at the stages of speech communication in more detail:

- Intention → Meaning: The typical reason for communication between people is that the speaker desires to change the mental state of the listener. Communication thus always starts with the intentions of the speaker. To achieve some specific communicative goal through language, the speaker must translate that intention into an utterance having some specific meaning. Provided that the chosen utterance meaning has the desired effect on the listener, the utterance does not need to be a direct encoding of the speaker's intention. For example, if you want your partner to make you a cup of tea, you might simply say "I'm feeling thirsty". Often a direct encoding of the intention is considered impolite, or can be counter-productive. If you need to know the time, you could say "Tell me the time", but that may not be as successful a strategy as the question "Can you tell me the time?". When we choose to communicate, the listener will not only consider the meaning of the utterance but ask herself "why did the speaker say that?". In this way, the listener recovers the speaker's intentions. This area of linguistic study is called Pragmatics; it considers how language is used for communication and what the speaker can assume of the listener and vice-versa.

- Meaning → Utterance: Given the requirement for an utterance having a desired meaning, the speaker constructs a suitable word sequence. Utterance meanings are composed by combining meanings of component words using the Grammatical Code. The speaker can explore their own repertoire of available words in combination with their knowledge of how word meanings can be combined using rules of sentence structure to derive a suitable utterance that would encode the desired meaning. The areas of linguistic study that relate word meanings to utterance meanings are called Syntax and Semantics.

- Utterance → Articulatory plan: The mental lexicon allows us to map the meanings of words to their pronunciation (and vice-versa). For example "small, furry, domesticated, carnivorous mammal" =

/kæt/ . In addition, literate persons are able to map entries in the mental lexicon to spelling: "small, furry, domesticated, carnivorous mammal" = "cat". Literate adults know many tens of thousands of word forms. In general the pronunciation of words is arbitrary and unrelated to their meaning. This is called the Phonological Code.Within any one language, speech articulations are used to encode a small number of distinctive pronunciation choices. While articulations and sounds are continuous in time and continuous in quality, these pronunciation choices are discrete. Differences of choice often change the identity of words. For example "cat" has three elements, each of which can be switched to create new words: "pat", "cot", "cap". These choices are often described in terms of selection from a small inventory of units called phonemes. English has about 20 vowel phonemes and about 20 consonant phonemes (depending on accent and how you count them). A dictionary will typically give you the pronunciation of a word from its spelling in terms of a phoneme sequence, e.g. "cat" =

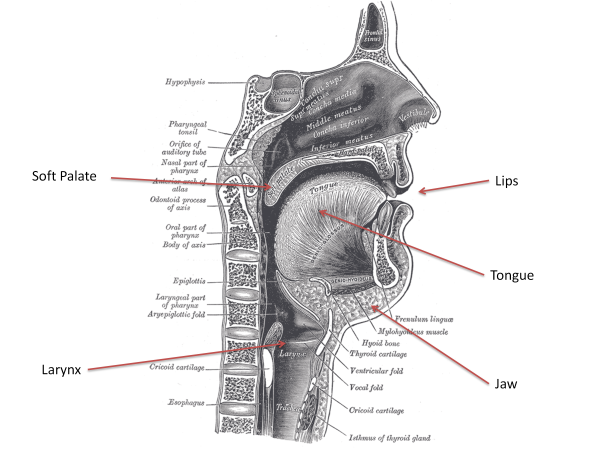

/k æ t/ . The linguistic study of the pronunciation choices used in a language is called Phonology. - Articulatory plan → Articulation: Speech sounds are generated by the vocal system, comprising the respiratory system and the speech articulators. The respiratory system delivers air at modest pressures, which can be used to create sources of sound. The articulators are the larynx, jaw, lips, tongue and soft-palate. The articulators are used to both generate sounds and to shape the sound quality that emerges from the lips and nostrils. Each pronunciation unit (phoneme) is associated with one or more articulatory movements or gestures, and the desired sequence of phonemes for an utterance needs to be converted into an economical sequence of articulatory movements. Since the articulators take time to move, the exact articulatory gesture for a phoneme will depend on what has just been articulated and on what is about to be articulated next. The linguistic study of articulation and sound is called Phonetics.

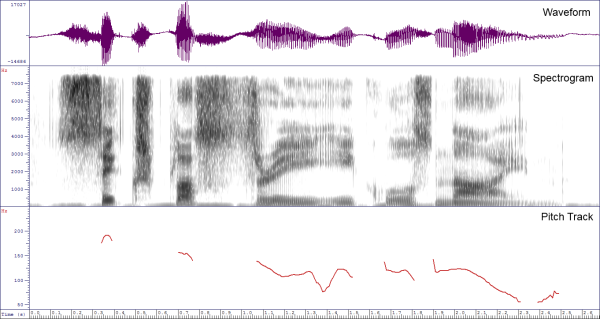

- Articulation → Sound: The movements of the articulators, synchronized with air flow from the lungs, causes sound to be generated and shaped. Sound generation is mostly caused by vibration of the vocal folds in the larynx or by turbulence created when air is forced through a narrow constriction. After a sound has been generated at some point in the vocal tract it can be further changed on its passage out of the mouth owing to the size and shape of the vocal tract pipe it passes through. The generated sound is radiated from the mouth and travels out from the speaker in all directions. We can capture the sound signal and represent it using graphs such as a waveform, a pitch track or a spectrogram. The study of the relationship between articulation and sound is called Acoustic-phonetics.

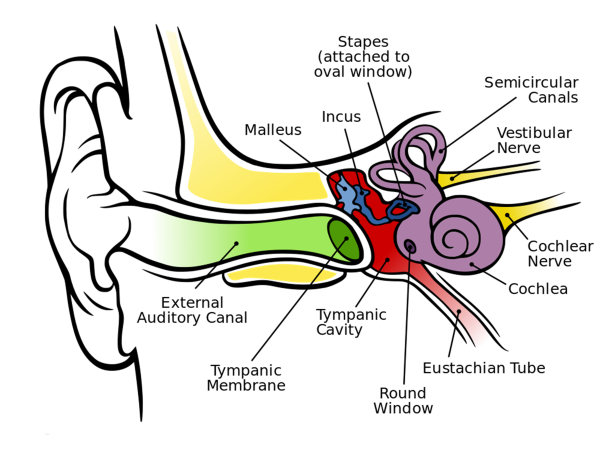

- Sound → Auditory response: At the listener, speech sounds are converted to neural activity in the auditory system, comprising the outer and middle ears, the cochlea and the neural pathways to the auditory cortex. Speech sounds give rise to sensations which vary in loudness, pitch and timbre, but which also vary over time. The study of the relationship between the physical and the psychological aspects of sound sensation is called Psychoacoustics.

- Auditory response → Word sequence: The speech perceptual system is tuned to listening out for sound differences which signal different phoneme categories. These are just those differences which are important for differentiating words. We are much better at hearing distinctions in our own language, for example, than we are for distinctions which are used in another language but not in ours. Sometimes the listener can see the speaker, and can also use visual information about mouth movement to help make distinctions between phoneme categories. Given an auditory sensation of speech (and optionally a visual sensation), the listener finds a word sequence which best explains the cause of the sensations. To determine the most likely word sequence the listener will call on a wide rage of knowledge: of the likely form of phonemes and their typical variation in context, knowledge of the speaker and the acoustic environment, knowledge of the words in the language, knowledge of accent and dialect variation, knowledge of likely word sequences, knowledge of likely utterance meanings, and knowledge of likely topics of conversation.

- Word sequence → Meaning: From the word sequence the listener recovers possible meanings for each word and possible meanings for the utterance. There is always much ambiguity in these interpretations, but the listener can choose ones which are most probable given the context.

- Meaning → Understanding: Finally the listener guesses at the communicative purpose of the utterance meaning - why would the speaker have said that? – to understand the speaker's intentions.

- A history of Phonetics in people and ideas

These are some of my personal highlights (with a UCL bias) - let me have your suggestions for additions.

Date Person or Idea 19th

cent.Alexander Ellis (1814-90) introduced the distinction between broad and narrow phonetic transcription. The former to indicate pronunciation without fine details, the latter to 'indicate the pronunciation of any language with great minuteness'. He also based symbols on the roman alphabet, just the IPA does today.

Henry Sweet (1845-1912) introduced the idea that the fidelity of broad transcription could be based on lexical contrast, the basis of the later phonemic principle. He also transcribed the "educated London speech" of his time, giving us the first insights into Received Pronunciation.

Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-94) was a physicist who applied ideas of acoustic resonance to the vocal tract and to the hearing mechanism.

Thomas Edison (1847-1931) invented sound recording which allowed careful listening and analysis of speech for the first time.

Paul Passy (1859-1940) was a founding member and the driving force behind the International Phonetic Association. He published the first IPA alphabet in 1888.

1900-

1929Daniel Jones (1881-1967) founded the Department of Phonetics at UCL and was its head from 1921-1947. He is famous for the first use of the term 'phoneme' in its current sense and for the invention of the cardinal vowel system for characterising vowel quality.

1930s The First International Congress of Phonetic Sciences was held in 1932 in Amsterdam.

Between 1928 and 1939, the Prague School gave birth to phonology as a separate field of study from phonetics. Key figures were Nikolai Trubetzkoy (1890-1938) and Roman Jakobson (1896-1982).

1940s Invention of the sound spectrograph at Bell Laboratories, 1946.

1950s Invention of the pattern playback (a kind of inverse spectrograph) at Haskins Laboratory, 1951. This was used for early experiments in speech perception.

Publication of R. Jakobson, G. Fant and M. Halle's Preliminaries to Speech Analysis, 1953. This presented the idea of distinctive features as a way to reconcile phonological analysis with acoustic-phonetic form.

Denis Fry (1907-1983) and Peter Denes built one of the very first automatic speech recognition systems at UCL, 1958. Watch a video here.

John R. Firth (1890-1960), working at UCL and at SOAS, introduces prosodic phonology as an alternative to monosystemic phonemic analysis.

1960s Early x-ray movies of speech collected at the cineradiographic facilty of the Wenner-Gren Research Laboratory at Nortull's Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, 1962.

First British English speech synthesized by rule, John Holmes, Ignatius Mattingly and John Shearme, 1964:

1970s Gunnar Fant (1919-2009) publishes Acoustic Theory of Speech Production, a ground-breaking work on the physics of speech sound production, 1970.

Development of the electro-palatograph (EPG), an electronic means to measure degree of tongue-palate contact, 1972.

Development of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), which allowed safe non-invasive imaging of our bodies for the first time, 1974.

Adrian Fourcin, working at UCL, describes the Laryngograph, a non-invasive means of measuring vocal fold contact, 1977.

Graeme Clark (1935-), working in Melbourne, Australia led a team that developed the first commercial cochlear implant (bionic ear), 1978.

1980s Dennis Klatt (-1988) develops the KlattTalk text-to-speech system, which became the basis for the DecTalk product, 1983:

Famously, DECTalk has been used by Stephen Hawking for so long that he is now recognised by its synthetic voice.First automatic speech dictation system developed at IBM by Fred Jelinek, Lalit Bahl and Robert Mercer among others, 1985.

Kai-fu Lee demonstrates Sphinx, the first large-vocabulary, speaker-independent, continuous speech recognition system, 1988.

1990s Development of Electro-magnetic articulography (EMA), a means to track the motion of the articulators in speaking in real time using small coils attached to the tongue, jaw and lips.

Publication of the TIMIT corpus of phonetically transcribed speech of 630 American talkers, 1993. This has been used as the basis for much research in acoustic-phonetics.

Jim and Janet Baker launch Dragon Systems Naturally Speaking continuous speech dictation system, 1997.

Increasing use of functional MRI to study the neural basis for language production and perception, 1997.

Ken Stevens (1924-2013) publishes Acoustic Phonetics, the most complete account yet of speech acoustics, 1999.

2000s Discovery of FOXP2, the first gene shown to have language-specific actions, 2001.

Microsoft include free text-to-speech and speech-to-text applications for the first time in Windows Vista, 2006.

2010s Development of real-time MRI that can be used to image the articulators during speech, 2010. Watch a video here.

Apple introduces the Siri spoken dialogue system. This was the first of many subsequent virtual assistants, 2011.

Advances in Electrocorticography (direct current measurements from the surface of the brain) allow us to study the patterns of neural excitation in the brain associated with speaking and listening in real-time. Recently there have been some astonishing new discoveries that challenge our understanding of how the brain speaks and listens, 2015.

New machine learning methods based on deep neural networks show speech recognition performance exceeding human abilities for the first time, 2016.

Readings

Essential

- Denes & Pison, The Speech Chain, W.H. Freeman, 1993. Chapter One - The Speech Chain - Available on Moodle.

- Miller, The Science of Words, Scientific American Library, 1991. Chapter One - The Scientific Study of Language - Available on Moodle.

Background

- Michael Ashby, Andrew Faulkner and Adrian Fourcin, "Research department of speech, hearing and phonetic sciences, UCL", The Phonetician 105-106, 2012. A brief sketch of the history and activities of my department.

Laboratory Activities

In this week's lab session you will explore how sounds differ from one another by recording some sounds and analysing them with graphical displays. This will help you understand the material in week 2 where we look at our hearing mechanism and how sound sensations relate to characteristics of the sound signal.

Reflections

You can improve your learning by reflecting on your understanding. Come to the tutorial prepared to discuss the items below.

- What is communicated through the speech chain?

- How might the fact that the listener can see the speaker help communication?

- How might the fact that the listener can hear himself/herself help communication?

- Think of an occasion where the meaning of an utterance is not composed from the meanings of the constituent words.

- Think of an occasion when the pronunciation of a word is related to its meaning.

- Think of an occasion when the intention of an utterance is precisely opposite to its meaning.

- Why don't we just say what we mean?

- Why do we need phonology (i.e. why are words made up from a small inventory of phonemes)? Why aren't whole words just treated as different sounds.

- Think of places in the speech chain where the communication of a message can go wrong.

Word count: . Last modified: 15:45 08-Jan-2020.